AI and the Registry of Power

I read the Atlas of AI, published in 2021 by Kate Crawford, and it is an astonishing read.

We are all quite familiar with the public image of Artificial Intelligence. It is easy to associate the text-to-image generation model Dall-E with the term, or translation software like DeepL, recommender systems used by Netflix or YouTube, and various forms of personal assistants such as Alexa or Siri. Even robots turn out to be a common first thought when talking about AI. But the vital point that Atlas of AI makes is that AI has long eclipsed its usage in mere consumer products and tools. Artificial Intelligence, Kate Crawford argues, is conquering a ”much wider set of political and social structures” and is “ultimately designed to serve existing dominant interests”. In a profound analysis backed by tremendous amounts of research, the book reveals to us that AI is primarily a “registry of power”, and that we should beware.

Crawford’s magnificent way of presenting us with this evidence is by telling stories that take us by the hand and say ‘Look, over there, this is the Silver Peak Lithium Mine, where residue from pumping up lithium brine gathers in large, toxic lakes.’, or ‘This is the Armour Beef dressing floor, where workers were the first to take their place in an assembly line, much as they do at Amazon today, where things are spiced up by automated time control.’ Not only are the examples historic, they are graphic, tangible, and they illustrate so well what is missing from our present conception of AI: The dirty, sweaty, greasy foundation on which it is built both materially, and, as it turns out, scientifically.

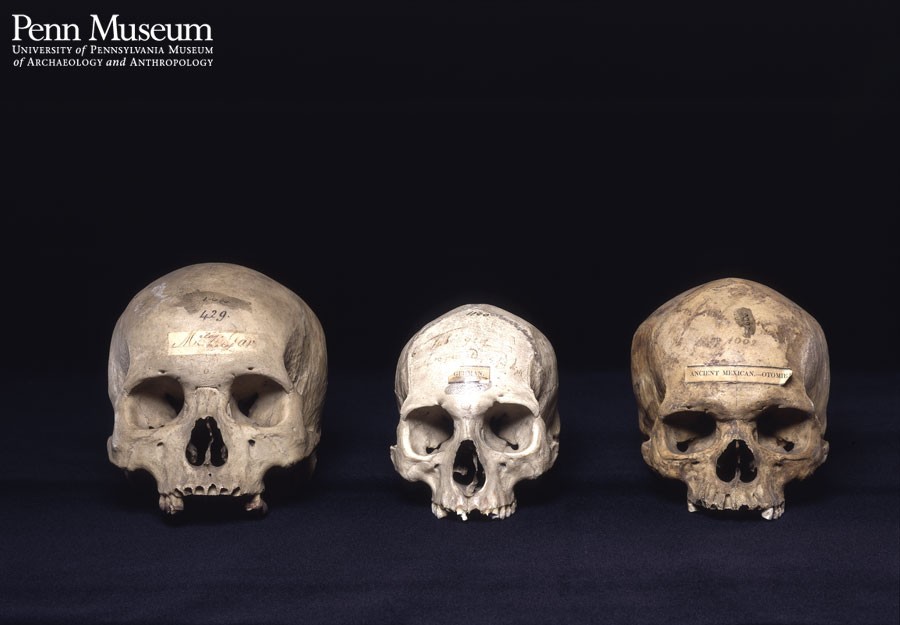

My favorite episode in this path of realization is Crawford’s visit to Samuel Morton’s cranial collection, a large amount of skulls gathered and labelled by the craniologist in the 19th century to explore if intelligence and “superiority” could be inferred from the size and structure of the human skull, establishing a deeply flawed and racist take on anatomy. This is the introduction to the book’s section on Classification and it is so rich in history and symbolism that it is nothing short of literary, and thus so suitable for the introduction of a central question: Who is the one holding the power to decide over what ought to be classified, and which classes to use? Of course, Crawford argues, the ones performing these classifications have rarely been the minorities and fringe groups, but the ruling class. It is no large leap of mind to realize that these classifications were not put in place in order to infringe on the ruling class’ control and influence, but to increase and cement them. The achievement of the Atlas of AI is not only to unveil the bizarre building blocks of present-day AI, but also to steer these questions back to the present, connecting them to discussions about bias and surveillance. After taking in the historic panorama that Crawford develops before us, we lastly arrive at the present with a quaint little image of a skull that reminds us of where it all started.

By leading us from the soil that is exploited for minerals to the integration of large-scale systems in government and military, Crawford carefully shows us how earth, labor, data, classification, state, power, and lastly, space, assume their roles as cogs in the large machinery that is AI. Each of these elements has secrets to tell and by the end we do not assume that anything about AI is without costs, only that they are hidden behind lofty curtains of marketing façade and a general, convenient confusion.

I do not want to tell you all the brilliant bits in advance. If you are interested in Artificial Intelligence, working in the field, or reflecting on it, then I wholeheartedly recommend this book and indeed urge you to read it. I had not thought about tracing AI by notions of geography and history in this manner, showing us just how closely connected to political power it is, and so it is not overstating to say that the Atlas of AI opened up my horizon by a considerable margin.

Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Kate Crawford, Yale University Press 2021.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Schmude, Timothée (Nov 2022). AI and the Registry of Power. https://timothee-schmude.github.io/.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{schmude2022ai-and-the-registry-of-power,

title = {AI and the Registry of Power},

author = {Schmude, Timothée},

year = {2022},

month = {Nov},

url = {https://timothee-schmude.github.io//blog/2022/ai-atlas/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: