Asking DALL·E About The Strongest Avenger; and Other Matters

You’ve probably heard about DALL·E, the huge neural network generating images from text, built on top of another huge neural network that is famously well-versed in human language: the Generative Pre-Trained Transformer 3, or GPT-3. So famous, in fact, that OpenAI decided that AI should not be open after all and sealed GPT-3 behind a wall of exclusivity only to be conquered by formal application or by, you know, paying. People that got through this application step tell intriguing tales about all the things that can be done with the model, among them GPT-3 trying pickup lines, GPT-3 writing books, GPT-3 composing poetry and GPT-3 doing basically everything else.

Setting aside the slightly dystopian implications for the moment, OpenAI in January last year announced yet another machine learning model with impressive capability: DALL·E. This one can generate images from any text that you give it, that is, it takes your words and tries to render a visual interpretation of them. The resulting images are not unlike those from DeepDream and thispersondoesnotexist.com (though those are different architectures). Apparently, the most intuitive thing to ask such a machine is to produce an image of a chair in the form of an avocado, which promptly became DALL·E’s emblem.

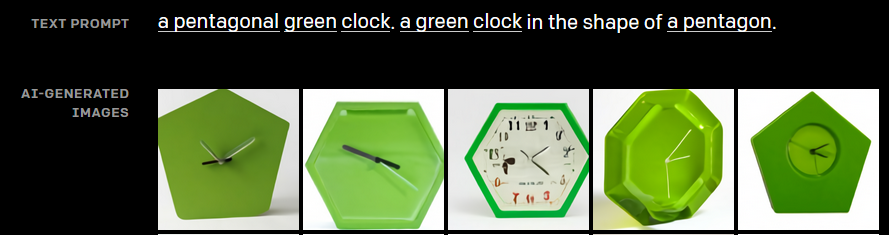

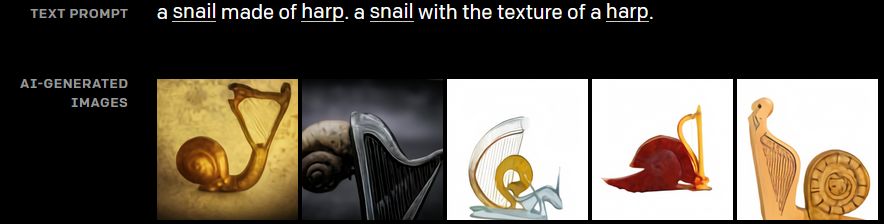

The name DALL·E is doubly punned, referring to our cute little order-obsessed robot WALL-E and the surrealist painter Dalí at the same time, and makes clear the intended crossover of algorithmic structure and artistic vision bordering on the subconscious. In theory this should result in a singular view on the world: a direct transport line between verbal imagination and graphic depiction, heavily influenced by whatever transformation the model performs on the input. And indeed the results appear to live up to this promise. Whether it imagines something realistic, like a pentagonal clock, or something more extraordinary, like a snail harp (images Copyright @ OpenAI 2021).

One is well advised not to forget the human part about these image generations. GPT-3, DALL·E’s base model, was trained on numerous texts from the web (the so-called Common Crawl and the whole of Wikipedia) and a lot of books. “Numerous” is understating: they are gigantic amounts. Towering, unimaginable amounts, impossible to grasp – you know the scales. The point is: most of this is human language. Every piece of text has an author, a date of publication, a context, and human views and opinions embedded deeply into it. This is no bad thing! It just means that when we are looking at GPT-3’s output, we are looking at the (mostly intransparent) transformation of a large volume of human language, cast into a specific form, like a distillation of everything that was said in the last 100 years – by certain people, in certain places.

On a side note: The process of transforming various inputs by the workings of an opaque machinery into something new actually sounds familiar – humans do it all the time. Of course, this is no clean analogy, there are multiple things we don’t understand about consciousness and the brain. Ironically though, we don’t understand everything about neural networks either. Our not-knowing how is a pretty straight parallel between the two concepts (and something we work on in our research project).

DALL·E was trained in a similar fashion to GPT-3: by collecting numerous text and image pairs from the internet, since it’s cheap and it’s there. One part comes from Wikipedia, the other part from Flickr. This means we get data from people hanging out on a) Wikipedia, and b) Flickr. Again, nothing to fret about necessarily, just something to keep in mind when looking at the applications of DALL·E. As a reminder, facial recognition systems couldn’t (or might still be unable to) handle images of black women as they were underrepresented in the training data. Thankfully, there are researchers occupying themselves with revealing and dealing with these discriminatory biases. Unluckily, big tech doesn’t always seem to like what they find and prefers to sanction them. Two prominent researches who left (or were made to leave) Google because of this are Margaret Mitchell and Timnit Gebru.

Coming back to the practical part of the model, you certainly would like to try your hands at it yourself. Good news! There is a mini version of DALL·E over at HuggingFace that let’s you play around with it, it is slow and not as good as the original, but still a lot of fun. You can also build the thing yourself, if you want, they put the code for DALL·E Mini on Github. (HuggingFace really are accommodating in giving access)

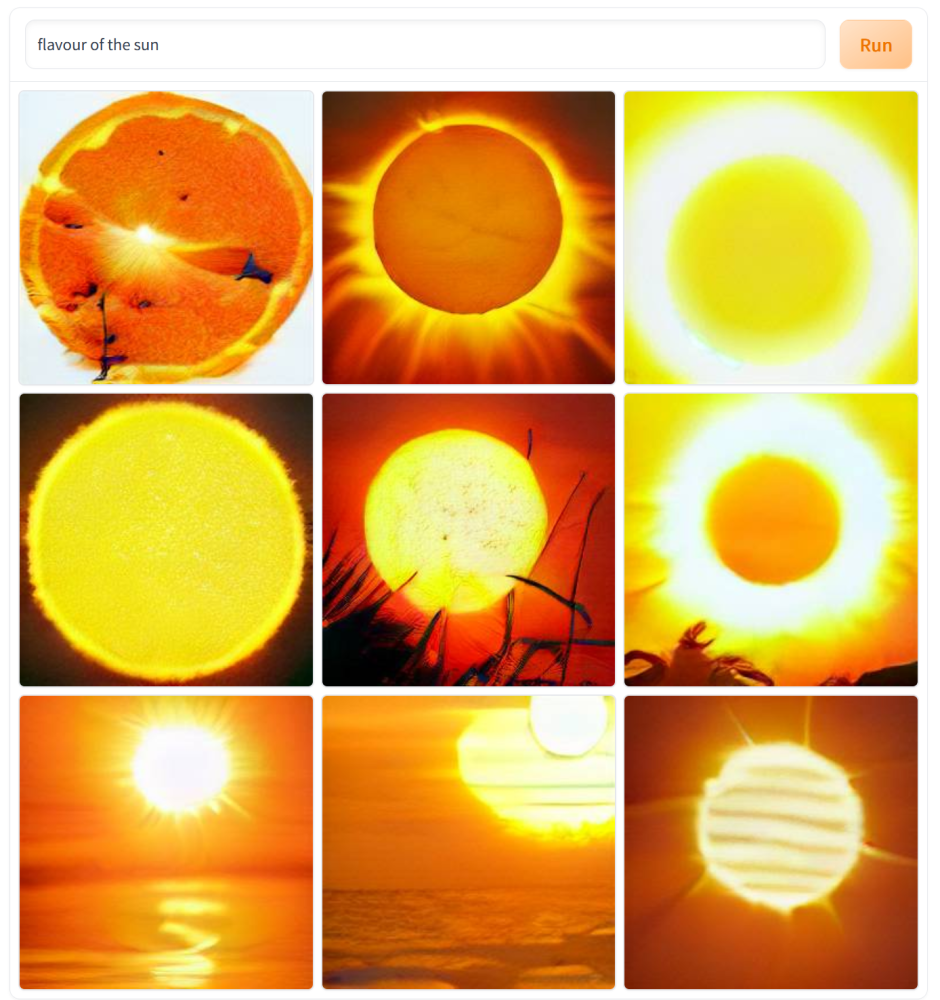

Alright, let’s see if it delivers! Avocado chairs and pentagon clocks fine and well, but what if we ask for things that can’t be pictured? Like the flavour of the sun?

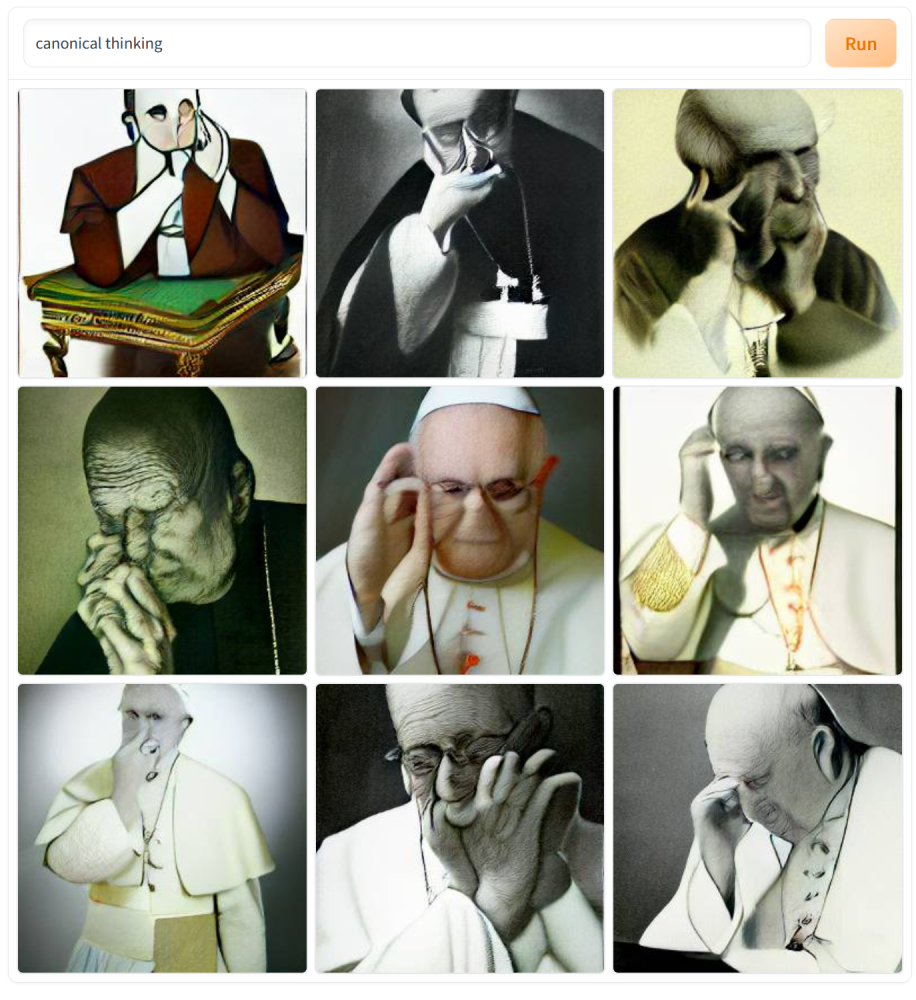

We could have figured there would be some orangey vibes in there. Let’s make it more abstract, let’s picture canonical thinking.

Whatever it is, the pope appears to have a part in it, and he really makes an effort, too. Not too surprising when you look at the meanings of “canonical”. One could make a sublime joke about the “literature pope” Marcel Reich-Ranicki, as he was called, who published the canon for German literature, but I think that’s going too far.

Let’s see what DALL·E does with something even more vague, a certain way of death, that the universe faces, provided some peculiar part of physics will turn out a specific way, the vacuum decay. In short, a bubble with a better energetic state than the present one that forms somewhere in space and makes everything nonexistent very quickly. No alt text provided for this image

Yep, that’s not so far off. There are bubbles, certainly, and Wikipedia has an image that virtually looks the same (don’t be confused it actually shows the Cosmic Microwave Background), so let’s settle on that being a truthful depiction of vacuum decay, no one can prove otherwise anyway.

Two to go, ordered by difficulty to answer. First one: Who is the strongest avenger?

Kind of all of them, I guess. Though Iron Man plays a central role, but maybe that’s just nostalgia.

Last question for the mini-AI-oracle and for our little excursion into strange AI imagination: What does life after death look like?

There is light, dark figures and a black vignette. If you do a google image search you will see that this is rather prototypical. Still, as a distillation of human ideas about life after death, this is not bad at all. As someone who also dove into literature analysis a couple of times, the possibility of interpreting symbolism and composition of these images is very intriguing. Incidentally, I have done something similar in my master’s thesis, but that’s a story for another time.

Suppose we had a fully working model of DALL·E, imagine the implications. Every photograph, be it for ads or articles, could be generated, every book cover, every movie poster, theoretically, every frame of a movie as well. This is science fiction, of course, but it slowly transcends into the realm of reality. Indeed, if you can make a profit on it, the thing is shoved into reality in the bat of an eye. And what do you know, there is a new version already! OpenAI presents: DALL·E 2.

The important question is, if AI was perfect, and if AI could generate every image possible, would you still look at a human one?

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: