Surprising and Irritating: How to get what people say using abductive analysis (in XAI)

This is a piece on qualitative methods and abductive analysis in explainable AI. Here’s the TL;DR: Talking to people is a good idea if you want to find out which explanations they need. But analysing what they tell you is a different story, especially if it’s surprising and confusing. To get the most out of it, abductive analysis has three recommendations: revisit your data, defamiliarize yourself, and use alternative theoretical casings. The list at the end explains what these mean.

Discovering people

Explainable AI is in the process of discovering that what you explain will not necessarily arrive at your audience the way you intended. Instead, your message will be jumbled and warped by all things separating you from them: the computer, the language, the difference in knowledge between you, the way in which you typically explain things to yourself, and so on. Graduating in Media Studies has its payoff at this (and only this) exact point – hear now a sacral choir chanting: “The medium is the message” (context).

Yes, but how does this help in explaining AI? At first, it only suggests to us to take a look beyond the idea of quantifying understanding and perceptions and get a good grasp of the human behind these metrics. In short: Speak to who you’re talking to. Doing so will yield quite surprising insights like ‘people tend to judge a system based on the institution deploying it’ [1] and ‘understanding has both rational and emotional facets’ [2]. These insights can then, with a bit of polishing and interpretation, be fed back into XAI to improve explanation design – at least that’s the idea.

Talking to people

Talking to people is a craft well established in the Social Sciences, which provide a plethora of methods, measures, and concepts to find out how people interact, acquire knowledge, and split the burden of understanding. After XAI discovered humans (I’m exaggerating), several researchers wrote papers that made an effort to build bridges to this fountain of wisdom that is the Social Sciences. Two of the rather important ones were Miller’s summary of things to know about human explanations [3] and Langer et al.’s model of people who have stakes in AI systems [4] (which, to be fair, is based on previous work by Arrieta et al. 2019 [5]). Finally, with a little shove from HCI – a field that discovered humans a good while back – a new sub-field emerged: Human-centred explainable AI, or HCXAI.

This is our ‘You are here’ red dot starting point: Explanations are not created in a vacuum nor do they arrive in one, so we would do good to consider all steps of the way. There is an argument to be made that XAI cannot possibly be responsible for how people process the information that we convey, and there might be ‘handoff’-point at which this might be true, but, personally, I feel we have not yet arrived there. Rather, we should first try to talk to all the stakeholders we identified two years back and find out what they would like to know.

Understanding what people say

This brings us to the practical, tutorial-like part of this text. I can now reveal that all of the above was pretence for an excuse to write about the obscure strand of qualitative research called ‘abductive analysis’ – and here we are! Do not quit yet! I’ll promise I’ll try to make it entertaining.

Imagine you talked to 30 people that you sourced from the local job agency in a very hot Viennese summer, something I’m incidentally most familiar with. You presented explanations about the system you are trying to study, recorded what people said in response and ended up with 30 one-hour interview transcripts. A giant amount of text for computer science standards, but a dwarf amount compared to what social scientists typically have to battle. The question that abductive analysis – and any qualitative analysis for that matter – tries to answer is: How do you make sense of all the things said?

There are two main and not too complex answers to this question: Either you dive into the data and build themes from what people said, or you tap into the literature to find your themes and then see if they connect to what people said. The first one is called inductive, the second one deductive analysis (and yes, I will draw the anger of the qualitative research gods with this simplified account).

While there exist strong opinions that either inductive or deductive analysis is the ground truth, a most intuitive way of going about analysing data like these interview transcripts is to combine the two. On the one hand, the literature certainly provides some topics that people typically talk about when trying to understand explanations of AI (such as fairness, the application context, and the technical details), on the other, you might well find things that the literature does not yet cover (such as the developer’s intention and the cost of deploying a model). So as not to spoil your naïve view, you first go through the transcripts and create categories from what you find in the data, and then you look into literature to see if anything matches. Indeed, some things were known before, others do neatly complement what’s already known, but then again, there is data that makes no sense at all. Why does participant 7-A not trust the study procedure? Why does participant 11-B talk about his relationship to his brother when asked about his understanding? And what do you do with the endless opinions that crop up all over your data (‘This whole algorithm thing is nonsense.’)?

Enter abductive analysis

Abductive analysis makes these idiosyncratic, inconvenient, confusing parts of the data a centrepiece of analysis. After all, why is it not apparent what these parts mean? Because their relation to the study goals is not clear, meaning they relate to something you did not consider, but which apparently does play a role in the real world and therefore – and this is the catch – will also play a role when your or anyone’s AI explanation will be used in the real world to provide information to this audience. This is an actual, not to be underestimated limitation.

There are three key parts to abductive analysis that all try to help you in producing interesting data and getting a hold of it to gain insight: revisiting, defamiliarization, and alternative casing. The whole idea goes back to Charles Peirce’s work from the 1930’s and is often summarized with the following triplet:

-

The surprising fact C is observed.

-

But if A were true, C would be a matter of course.

-

Hence, there is a reason to suspect that A is true. [6]

You will be glad to hear there’s more up-to-date literature describing the method, namely Timmermans’ and Tavory’s paper from 2012 [7] and their book from 2014 [8]. More or less helpfully, they explain:

“[A]bduction is the form of reasoning through which we perceive the phenomenon as related to other observations either in the sense that there is a cause and effect hidden from view, in the sense that the phenomenon is seen as similar to other phenomena already experienced and explained in other situations, or in the sense of creating new general descriptions.” [7]

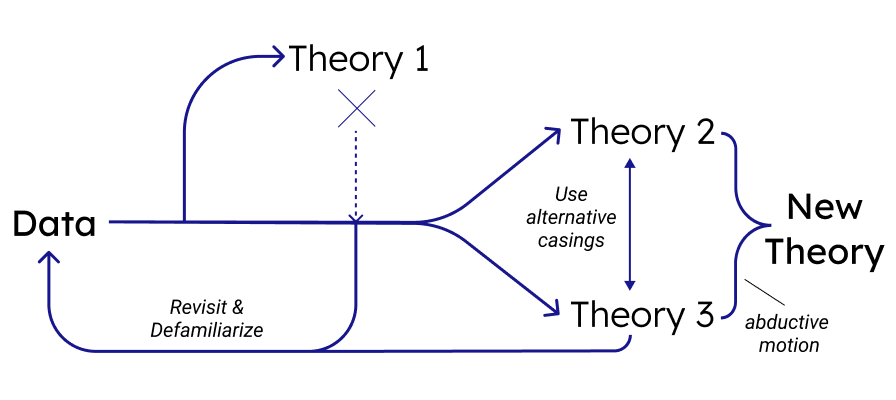

In an effort to ground the whole thing, they add that everyone performs abduction whenever they experience something surprising in their life, drawing from their existent knowledge to incorporate the new observations. Two aspects helped me to get into this train of thought: First, ‘abducting’ means leading away: surprising insights lead us away from known theories to new ones. Second, the position of the researcher is important: depending on what you know and how you think, you will produce other insights than the next person, even if you’re from the same field. I put together a diagram for myself that semi-aptly tries to capture the idea. My idea of how abductive analysis arrives at theory: Explanations for surprising evidence are considered and applied by revisiting and defamiliarizing data. Finally, when no theory sufficiently explains a piece of data, a new theory is created.

The how-to of abductive analysis

In the spirit of a true crash course I will close this method piece with an attempt to give you something practical to try out (but please do read the paper before trying this at home). Here is my interpretation of how to apply the trinity of abductive analysis in your qualitative work:

- Revisit the phenomenon: Qualitative data is overwhelming, our perception can’t handle all of it in one go. Take time, let the data lie for a bit and come back with fresh eyes. Check your field notes, write memos, try to re-experience your data over a stretch of time and you will find that there’s more to see every time you come back

- Defamiliarize yourself: What you know guides what you perceive. Try to alienate yourself from your data, estrange the familiar, put your textual data in spoken word and vice versa to notice things you previously took for granted. Where revisiting is about perceiving data at different times, defamiliarization is about perceiving it from a semantic distance

- Use alternative casings: Theories serve as guidelines for how we analyse data, changing theories means changing guidelines. Connect your data to multiple theoretical frameworks to understand the data in as many ways as possible. When analysing data is a puzzle, changing our theoretical positionality will present us with a new puzzle to solve each time. [7, 8]

And with that I leave you. My feelings towards abductive analysis are of fascination and confusion in equal parts and indeed I have turned and twisted these ideas in my head for a few weeks now, trying to find a perspective that allows for easy application. Despite the title of this article, what perspectives I have found so far don’t take the form of a manual, but rather lead to a change in consciousness for how empirical studies allow us to gather and understand data. In my case, it sparked confidence that producing surprising and irritating data is not only allowed, but even desirable.

Inspiring or puzzling? Do let me know what you think about abduction!

Here are the references used:

[1] Anna Brown, Alexandra Chouldechova, Emily Putnam-Hornstein, Andrew Tobin, and Rhema Vaithianathan. 2019. Toward Algorithmic Accountability in Public Services: A Qualitative Study of Affected Community Perspectives on Algorithmic Decision-making in Child Welfare Services. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, Glasgow Scotland Uk, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300271

[2] Timothée Schmude, Laura Koesten, Torsten Möller, and Sebastian Tschiatschek. 2023. On the Impact of Explanations on Understanding of Algorithmic Decision-Making. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (Chicago, IL, USA) (FAccT ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 959–970. https://doi.org/10.1145/3593013.3594054

[3] Tim Miller. 2019. Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence 267 (Feb. 2019), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2018.07.007

[4] Markus Langer, Daniel Oster, Timo Speith, Holger Hermanns, Lena Kästner, Eva Schmidt, Andreas Sesing, and Kevin Baum. 2021. What do we want from Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)? – A stakeholder perspective on XAI and a conceptual model guiding interdisciplinary XAI research. Artificial Intelligence 296 (July 2021), 103473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2021.103473

[5] A. B. Arrieta, N. Díaz-Rodríguez, J. D. Ser, A. Bennetot, S. Tabik, A. Barbado, S. Garcia, S. GilLopez, D. Molina, R. Benjamins, R. Chatila, F. Herrera. 2020. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI, Information Fusion 58, p. 82–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2019.12.012

[6] Peirce Charles. 1934. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. vol. 5, Pragmatism and Pragmaticism, edited by Hartshorne C., Weiss P. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[7] Stefan Timmermans and Iddo Tavory. 2012. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociological Theory 30, 3, 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914

[8] Ido Tavory and Stefan Timmermans. 2014. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research. University of Chicago Press, United States

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Schmude, Timothée (Nov 2023). Surprising and Irritating: How to get what people say using abductive analysis (in XAI). https://timothee-schmude.github.io/.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{schmude2023surprising-and-irritating-how-to-get-what-people-say-using-abductive-analysis-in-xai,

title = {Surprising and Irritating: How to get what people say using abductive analysis (in XAI)},

author = {Schmude, Timothée},

year = {2023},

month = {Nov},

url = {https://timothee-schmude.github.io//blog/2023/abduction/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: